Flow and handling to minimize feline stress in the shelter environment

By Rebecca Rauwald, 4th year veterinary student at University of Wisconsin-Madison and Dane County Humane Society veterinary student extern

Feline stress is an important factor in the health and welfare of shelter cats. Psychological stress contributes to lower resistance to infectious disease and may play a role in idiopathic Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease (FLUTD), a relatively common cause of litterbox problems in cats. Furthermore, less fearful cats are often easier to handle and friendlier. This helps to make the job of shelter staff easier, more enjoyable, and safer. Cats may interact more positively with potential adopters and may be adopted sooner. This means a shorter length of stay, and an increased capacity for care in the shelter overall.

From the moment a cat enters the shelter environment to the moment it leaves, there are important steps that can be taken to try to minimize stress, enhance each cat’s ability to cope with stress, and maximize feline welfare in the shelter environment. When possible it is important to have separate areas for entry of cats and dogs in your shelter. In general cats should be kept in a quiet area and should not be exposed to sounds of barking dogs, ringing phones, lots of chatting people or other loud noises. Consider playing soft music or white noise in housing areas. Pheromone diffusers may be a useful adjunct to diminish stress. As has been previously discussed, it is important for every cat to have a hiding place. See last month’s article for more details on this subject.

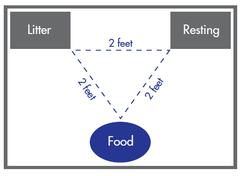

Housing plays an important role in helping cats to cope with the stress of entering the shelter environment. A thorough discussion of housing is beyond the scope of this article, so only a few key points will be discussed. However, if you would like more information, the Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters are available online from the Association of Shelter Veterinarians (see references below). The size of the cage should allow for ample separation between the cat's resting place, its litterbox and food/water bowls. The adjacent figure illustrates the minimum recommended distances between these areas for cats according to the Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters. Ideally, each cat should have 6-8 square feet of floor space and enough height to accommodate a hiding box.

When working with cats for exams, it is important to recognize the signs of stress in different cats. Initially stressed cats may freeze silently or casually walk away. But if these signs are missed and improper actions taken, the cat’s behavior may progress to a fractious, untreatable cat. When first entering a shelter, every cat is experiencing stress to some degree, though individuals express it in different ways. Examples include:

Defensive behavior: creates space between the cat and a perceived threat, manifested as hissing, spitting, vocalizing, striking out, and other behaviors typically described as aggression.

Inhibition: a reduction in normal behaviors such as urination, defecation, grooming, feeding, approachability and mobility; these cats may appear to sleep most of the time.

Disruption: manipulating their environment and cage contents to create physical barriers or hiding places.

It is very important to recognize the wide spectrum of behaviors that indicate stress in a cat so that accurate assessments and decisions regarding placement can be made.

When handling cats in the shelter, it is important for staff to be flexible in their approach to interacting with each individual cat. Handling that is harsh or overly restrictive for an individual cat can make that cat struggle more or develop aversive behaviors with repeated handling. First, it is important to work with cats in a safe, quiet environment. Close all portals into the room and limit traffic in and out of the area. The area should be cleared of debris, clutter and other animals. Use towels or blankets to cover slippery surfaces. People should avoid looming over, staring at, and reaching quickly for cats. If a cat’s body posture indicates they do not find petting comforting or rewarding (cringing, flinching or trying to move away), it should be avoided. When carrying or moving to restrain a cat, support him well. When possible also allow them to support some part of their body rather than lifting them completely into the air. NEVER lift a cat or suspend its body weight by “scruffing” alone; this may be painful and makes most cats very anxious.

While working with a cat attempt to use the minimal restraint needed for the individual. avoid letting her move around frantically or out of control. Always be ready to tighten your hold or change your hand and body position in case he suddenly tries to escape or struggles. However, This does not mean holding a cat carelessly or allowing her to squirm and get loose. It means avoiding automatically scruffing cats, holding them in a death grip, or pinning them down. Recognize that all cats, including the friendliest, might bite due to pain, fright, strange sounds, smells and people. It is important to always let the person you are working with know if you are losing control of the cat. When working with defensive cats, start by trying to cover their head or whole body using a cat muzzle or a towel. These are not used to immobilize the cat but to calm them. If further restraint is needed for a wiggly cat, there are various versions of “kitty burritos” that can aid in keeping cats and handlers safe. Move slowly and deliberately, minimize hand gestures or sudden movements and speak in a calm, quiet voice.

Work with cats in a “stop and go” pattern if needed. When they start to show signs of resistance to your exam or procedure, give them a short break for petting or allow them to move around a bit, then restart again. Prepare treat-syringes in advance filled with smelly canned food, squeeze cheese, or Kong liver paste or use fun toys to distract cats; this will not work for all cats but for some is a great way to break the ice. When performing multiple procedures, begin with the least stressful or invasive. Change needles between drawing up an injection and administering it to the cat to minimize discomfort. Gloves and nets are useful tools in some situations, though both place significant limitations on a handler’s ability to restraint or perform procedures on a cat.

For further information on handling practices that minimize feline stress there are great resources to be found at the website of veterinarian and animal behaviorist Dr. Sophia Yin at drsophiayin.com, and the American Association of Feline Practitioners ‘Feline-Handling Guidelines’ at http://www.isfm.net/wellcat/UK/FFHG.pdf.

References

AAFP and ISFM Feline-Friendly Handling Guidelines. Rodan, I. et al. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery (2011) 13, 364–375

Association of Shelter Veterinarians Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters. http://www.sheltervet.org/about/shelter-standards/

Feline Handling to Prevent Pain and Distress. Ilona Rodan, DVM, DABVP (Feline Practice). Atlantic Coast Veterinary Conference 2011. Accessed on VIN.com

Feline Stress, Housing and Wellness. Kate Hurley DVM, MPVM, Koret Shelter Medicine Program, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine http://sheltermedicine.com/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/fel_housing_stress_2011.pdf

Improving the Welfare of Cats in Practice. Sandra McCune, VN, BA(Mod), PhD WSAVA/FECAVA/BSAVA World Congress 2012. Accessed on VIN.com.

Low Stress Handling of Difficult Cats. Sophia Yin, DVM, MS. VIN.com Rounds transcript.

Low Stress Handling & Restraint of Fractious Cats & Dogs. Sophia Yin, DVM, MS. Western Veterinary Conference 2011

Feline stress is an important factor in the health and welfare of shelter cats. Psychological stress contributes to lower resistance to infectious disease and may play a role in idiopathic Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease (FLUTD), a relatively common cause of litterbox problems in cats. Furthermore, less fearful cats are often easier to handle and friendlier. This helps to make the job of shelter staff easier, more enjoyable, and safer. Cats may interact more positively with potential adopters and may be adopted sooner. This means a shorter length of stay, and an increased capacity for care in the shelter overall.

From the moment a cat enters the shelter environment to the moment it leaves, there are important steps that can be taken to try to minimize stress, enhance each cat’s ability to cope with stress, and maximize feline welfare in the shelter environment. When possible it is important to have separate areas for entry of cats and dogs in your shelter. In general cats should be kept in a quiet area and should not be exposed to sounds of barking dogs, ringing phones, lots of chatting people or other loud noises. Consider playing soft music or white noise in housing areas. Pheromone diffusers may be a useful adjunct to diminish stress. As has been previously discussed, it is important for every cat to have a hiding place. See last month’s article for more details on this subject.

Housing plays an important role in helping cats to cope with the stress of entering the shelter environment. A thorough discussion of housing is beyond the scope of this article, so only a few key points will be discussed. However, if you would like more information, the Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters are available online from the Association of Shelter Veterinarians (see references below). The size of the cage should allow for ample separation between the cat's resting place, its litterbox and food/water bowls. The adjacent figure illustrates the minimum recommended distances between these areas for cats according to the Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters. Ideally, each cat should have 6-8 square feet of floor space and enough height to accommodate a hiding box.

When working with cats for exams, it is important to recognize the signs of stress in different cats. Initially stressed cats may freeze silently or casually walk away. But if these signs are missed and improper actions taken, the cat’s behavior may progress to a fractious, untreatable cat. When first entering a shelter, every cat is experiencing stress to some degree, though individuals express it in different ways. Examples include:

Defensive behavior: creates space between the cat and a perceived threat, manifested as hissing, spitting, vocalizing, striking out, and other behaviors typically described as aggression.

Inhibition: a reduction in normal behaviors such as urination, defecation, grooming, feeding, approachability and mobility; these cats may appear to sleep most of the time.

Disruption: manipulating their environment and cage contents to create physical barriers or hiding places.

It is very important to recognize the wide spectrum of behaviors that indicate stress in a cat so that accurate assessments and decisions regarding placement can be made.

When handling cats in the shelter, it is important for staff to be flexible in their approach to interacting with each individual cat. Handling that is harsh or overly restrictive for an individual cat can make that cat struggle more or develop aversive behaviors with repeated handling. First, it is important to work with cats in a safe, quiet environment. Close all portals into the room and limit traffic in and out of the area. The area should be cleared of debris, clutter and other animals. Use towels or blankets to cover slippery surfaces. People should avoid looming over, staring at, and reaching quickly for cats. If a cat’s body posture indicates they do not find petting comforting or rewarding (cringing, flinching or trying to move away), it should be avoided. When carrying or moving to restrain a cat, support him well. When possible also allow them to support some part of their body rather than lifting them completely into the air. NEVER lift a cat or suspend its body weight by “scruffing” alone; this may be painful and makes most cats very anxious.

While working with a cat attempt to use the minimal restraint needed for the individual. avoid letting her move around frantically or out of control. Always be ready to tighten your hold or change your hand and body position in case he suddenly tries to escape or struggles. However, This does not mean holding a cat carelessly or allowing her to squirm and get loose. It means avoiding automatically scruffing cats, holding them in a death grip, or pinning them down. Recognize that all cats, including the friendliest, might bite due to pain, fright, strange sounds, smells and people. It is important to always let the person you are working with know if you are losing control of the cat. When working with defensive cats, start by trying to cover their head or whole body using a cat muzzle or a towel. These are not used to immobilize the cat but to calm them. If further restraint is needed for a wiggly cat, there are various versions of “kitty burritos” that can aid in keeping cats and handlers safe. Move slowly and deliberately, minimize hand gestures or sudden movements and speak in a calm, quiet voice.

Work with cats in a “stop and go” pattern if needed. When they start to show signs of resistance to your exam or procedure, give them a short break for petting or allow them to move around a bit, then restart again. Prepare treat-syringes in advance filled with smelly canned food, squeeze cheese, or Kong liver paste or use fun toys to distract cats; this will not work for all cats but for some is a great way to break the ice. When performing multiple procedures, begin with the least stressful or invasive. Change needles between drawing up an injection and administering it to the cat to minimize discomfort. Gloves and nets are useful tools in some situations, though both place significant limitations on a handler’s ability to restraint or perform procedures on a cat.

For further information on handling practices that minimize feline stress there are great resources to be found at the website of veterinarian and animal behaviorist Dr. Sophia Yin at drsophiayin.com, and the American Association of Feline Practitioners ‘Feline-Handling Guidelines’ at http://www.isfm.net/wellcat/UK/FFHG.pdf.

References

AAFP and ISFM Feline-Friendly Handling Guidelines. Rodan, I. et al. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery (2011) 13, 364–375

Association of Shelter Veterinarians Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters. http://www.sheltervet.org/about/shelter-standards/

Feline Handling to Prevent Pain and Distress. Ilona Rodan, DVM, DABVP (Feline Practice). Atlantic Coast Veterinary Conference 2011. Accessed on VIN.com

Feline Stress, Housing and Wellness. Kate Hurley DVM, MPVM, Koret Shelter Medicine Program, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine http://sheltermedicine.com/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/fel_housing_stress_2011.pdf

Improving the Welfare of Cats in Practice. Sandra McCune, VN, BA(Mod), PhD WSAVA/FECAVA/BSAVA World Congress 2012. Accessed on VIN.com.

Low Stress Handling of Difficult Cats. Sophia Yin, DVM, MS. VIN.com Rounds transcript.

Low Stress Handling & Restraint of Fractious Cats & Dogs. Sophia Yin, DVM, MS. Western Veterinary Conference 2011