Feline infectious peritonitis, a complex disease

By Kimberly Shaffer, 4th year veterinary student at University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Dane County Humane Society veterinary student extern

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a complex disease with a misleading title, as the disease is not infectious or contagious from cat to cat. For FIP to develop, there needs to be the correct combination of individual host factors and virus factors. To understand FIP, one must first learn its relationship to feline coronavirus.

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a complex disease with a misleading title, as the disease is not infectious or contagious from cat to cat. For FIP to develop, there needs to be the correct combination of individual host factors and virus factors. To understand FIP, one must first learn its relationship to feline coronavirus.

|

Feline Corona Virus vs. FIP:

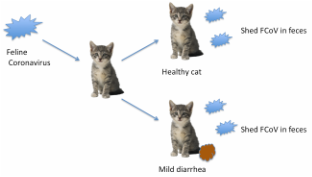

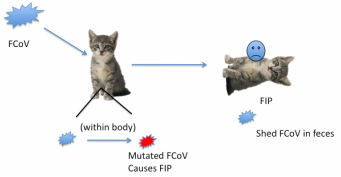

What is feline coronavirus (FCoV)? FCoV is a common virus of cats that infects the cells of the gastrointestinal tract. The majority of cats infected with FCoV will remain healthy and show no signs of disease, while a minority may develop mild diarrhea. This virus is particularly common in multi-cat environments, such as animal shelters or breeding catteries. Approximately 80-90% of cats in animal shelters and other multi-cat environments have been exposed to FCoV, usually early on in life as the protective maternal antibodies they got from their mothers are waning. How are feline coronavirus and feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) related? The disease FIP develops when a mutation occurs within the feline coronavirus strain within a given cat. This mutation allows the virus to replicate and survive in cells outside of the gastrointestinal tract—in the blood and in the tissue of organs. Cats are not infected directly with the mutated virus that causes FIP; rather this mutation occurs within the body after infection with FCoV. The response of the individual cats’ immune system to the virus also plays a role in whether FIP develops. FIP develops in cats whose immune systems do not mount an effective attack against the mutated virus. It is not fully understood why only some cats can mount an effective immune response. Approximately 10-12% of cats infected with FCoV will go on to develop FIP in the weeks to months and rarely even years following infection with FCoV. |

Are certain cats more likely to develop FIP if they are infected with FCoV?

Yes, there are “risk factors” that put certain cats at a higher risk of developing FIP than others, but there is no way to predict which exact cats in a group of animals will develop the disease.

Cats with weakened immune systems are at a greater risk of developing FIP. Thus, the majority of cats who develop FIP are kittens or cats over 13 years of age, particularly those exposed to forms of stress. Sources of stress can include crowded, dirty living environments, recent surgery, recent transportation or re-homing, and co-infection with other diseases, such as feline leukemia virus.

Certain breeds of cats and particular family lines have also shown to be at a higher risk of developing FIP. The littermates of a kitten who develops FIP are at a substantially greater risk of developing the disease than an unrelated kitten in the same environment.

How does FCoV spread from cat to cat?

The most common way FCoV spreads between cats is from contact with contaminated litter boxes, as the virus is shed in feces. Some cats may become “carriers” meaning they will show no signs of disease, but will continue to shed the virus in their feces for months to years.

The mutated feline coronavirus that causes FIP is not transmitted from cat to cat, as it is associated with cells contained in the blood and in organs and is therefore not shed in feces.

Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment:

What are the symptoms of FIP?

There are two forms of FIP, the “wet form” and the “dry form”. There are several possible presentations with either form of FIP with signs that could be attributable to many other diseases. Cats with either form of FIP may be lethargic and have decreased appetites, weight loss, and fevers that do not respond to antibiotics. Other cats may remain bright and alert with a good appetite, but lose weight for no identifiable reason. Any organ can be affected by FIP, and signs of damage are widely variable. Other signs of the “wet form” of FIP include fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity (“ascites”) and in the chest cavity (“thoracic effusion”). Cats with ascites may have a “potbellied” appearance.

How is FIP diagnosed and treated?

Unfortunately there is no simple, noninvasive test for FIP in a live cat. The only way to definitively diagnose FIP is to find the virus in cells in a tissue sample from an organ. As it is often impractical to take a surgical biopsy in a live, sick cat, a suspect diagnosis of FIP is most often based on a collection of suggestive clinical signs, blood work, and abdominal fluid analysis.

There is no cure for FIP and it is always eventually fatal. There are some medications that may make cats more comfortable and improve their quality of life for a short time, but all infected cats will eventually require humane euthanasia or succumb to the disease.

There is a blood test for feline coronavirus. Can this test be used to diagnose FIP?

A positive blood test for FCoV indicates that the cat has been exposed to FCoV. As discussed above, the majority of cats who are exposed to FCoV do not go on to develop FIP. There is no blood test that detects the mutated form of FCoV that causes FIP.

Outbreaks and Prevention:

If FIP cannot be spread cat to cat, then how do outbreaks occur?

Outbreaks, or an increased number of confirmed FIP cases in a given population of cats, are rare but can and do occur, most commonly in mutli-cat environments, such as animal shelters or breeding catteries. At this time, FIP outbreaks are not well understood, but there are some key factors that likely contribute to outbreaks. There are certain more “virulent” strains of FCoV that seem more likely to mutate into FIP. There is also evidence that cats with prolonged exposure to high doses of FCoV in the environment may more readily develop FIP.

If an FIP outbreak does occur in a shelter, how can it be controlled?

Unfortunately, outbreaks are hard to control because FIP is not directly infectious, is a hard disease to diagnose, and has no effective vaccine. Since the majority of cats in a shelter have been exposed to FCoV, there is no practical way to quarantine “exposed” cats.

During a FIP outbreak, the methods of good hygiene and stress reduction that are used to prevent any disease transmission should be continued vigilantly. Since FCoV is transmitted by contact with infected feces, the best method of prevention is proper hygiene, frequent litter box cleaning, and placing food bowls far away from litter boxes. Although FCoV can survive in the environment, common disinfectants and detergents easily destroy the virus.

For more information, please consult the following references and resources.

References:

Yes, there are “risk factors” that put certain cats at a higher risk of developing FIP than others, but there is no way to predict which exact cats in a group of animals will develop the disease.

Cats with weakened immune systems are at a greater risk of developing FIP. Thus, the majority of cats who develop FIP are kittens or cats over 13 years of age, particularly those exposed to forms of stress. Sources of stress can include crowded, dirty living environments, recent surgery, recent transportation or re-homing, and co-infection with other diseases, such as feline leukemia virus.

Certain breeds of cats and particular family lines have also shown to be at a higher risk of developing FIP. The littermates of a kitten who develops FIP are at a substantially greater risk of developing the disease than an unrelated kitten in the same environment.

How does FCoV spread from cat to cat?

The most common way FCoV spreads between cats is from contact with contaminated litter boxes, as the virus is shed in feces. Some cats may become “carriers” meaning they will show no signs of disease, but will continue to shed the virus in their feces for months to years.

The mutated feline coronavirus that causes FIP is not transmitted from cat to cat, as it is associated with cells contained in the blood and in organs and is therefore not shed in feces.

Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment:

What are the symptoms of FIP?

There are two forms of FIP, the “wet form” and the “dry form”. There are several possible presentations with either form of FIP with signs that could be attributable to many other diseases. Cats with either form of FIP may be lethargic and have decreased appetites, weight loss, and fevers that do not respond to antibiotics. Other cats may remain bright and alert with a good appetite, but lose weight for no identifiable reason. Any organ can be affected by FIP, and signs of damage are widely variable. Other signs of the “wet form” of FIP include fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity (“ascites”) and in the chest cavity (“thoracic effusion”). Cats with ascites may have a “potbellied” appearance.

How is FIP diagnosed and treated?

Unfortunately there is no simple, noninvasive test for FIP in a live cat. The only way to definitively diagnose FIP is to find the virus in cells in a tissue sample from an organ. As it is often impractical to take a surgical biopsy in a live, sick cat, a suspect diagnosis of FIP is most often based on a collection of suggestive clinical signs, blood work, and abdominal fluid analysis.

There is no cure for FIP and it is always eventually fatal. There are some medications that may make cats more comfortable and improve their quality of life for a short time, but all infected cats will eventually require humane euthanasia or succumb to the disease.

There is a blood test for feline coronavirus. Can this test be used to diagnose FIP?

A positive blood test for FCoV indicates that the cat has been exposed to FCoV. As discussed above, the majority of cats who are exposed to FCoV do not go on to develop FIP. There is no blood test that detects the mutated form of FCoV that causes FIP.

Outbreaks and Prevention:

If FIP cannot be spread cat to cat, then how do outbreaks occur?

Outbreaks, or an increased number of confirmed FIP cases in a given population of cats, are rare but can and do occur, most commonly in mutli-cat environments, such as animal shelters or breeding catteries. At this time, FIP outbreaks are not well understood, but there are some key factors that likely contribute to outbreaks. There are certain more “virulent” strains of FCoV that seem more likely to mutate into FIP. There is also evidence that cats with prolonged exposure to high doses of FCoV in the environment may more readily develop FIP.

If an FIP outbreak does occur in a shelter, how can it be controlled?

Unfortunately, outbreaks are hard to control because FIP is not directly infectious, is a hard disease to diagnose, and has no effective vaccine. Since the majority of cats in a shelter have been exposed to FCoV, there is no practical way to quarantine “exposed” cats.

During a FIP outbreak, the methods of good hygiene and stress reduction that are used to prevent any disease transmission should be continued vigilantly. Since FCoV is transmitted by contact with infected feces, the best method of prevention is proper hygiene, frequent litter box cleaning, and placing food bowls far away from litter boxes. Although FCoV can survive in the environment, common disinfectants and detergents easily destroy the virus.

For more information, please consult the following references and resources.

References:

- Feline Infectious Peritonitis/Feline Enteric Coronavirus (FIP/FECV) Information Sheet. Accessed on www.sheltermedicine.com.

- Feline Infectious Peritonitis, ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. Addie, Diane et al. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery (2009) 11, 594-604.

- Feline Infectious Peritonitis Information Sheet. Accessed on www.vet.cornell.edu

- Update on Feline Infectious Peritonitis. Melissa A. Kennedy, DVM, PhD, DACVM. Modified from an article originally published Vet Med. (2009) 104, 384-392. Accessed on VIN.com

- FIP: An Overview. Alice Wolf, DVM, DACVIM, ABVP (Fe). Accessed on VeterinaryPartner.com